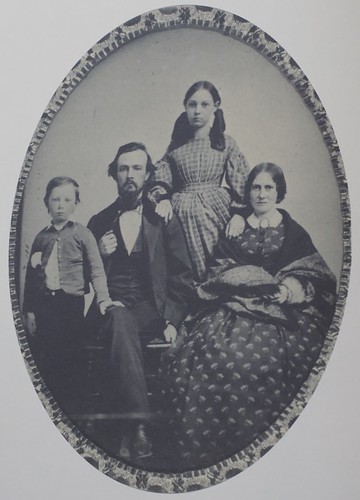

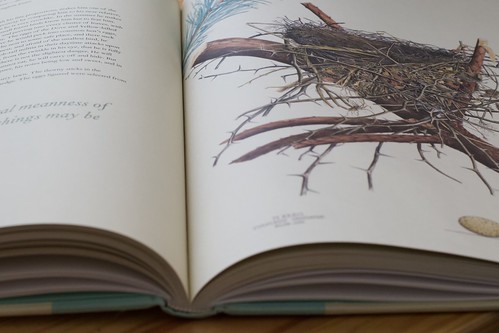

A wood thrush nest, illustrated by Genevieve Jones, a naturalist and self-taught scientific illustrator. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

Science and art come together in the extraordinary book “America’s Other Audubon,†which tells of an energetic and intelligent young woman’s response to a life restricted by lack of marriage and education, and her family’s determination to make her life’s work a reality after she died young.

For more than a century, ornithologists and natural historians consulted the exquisite and scientifically accurate drawings in “Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio” to help them identify items from their own collections. But few others knew the book existed, and fewer still the story of the young woman who hatched the idea: Genevieve Jones (1847-1879).

Genevieve Jones. Photo from the Pickaway County Historical and Genealogical Society, Circleville, Ohio.

Genevieve and her book would have remained in obscurity were it not for librarian Joy M. Kiser. Kiser recognized that the book, ambitious and technical, was equally rare for how it came into being, according to Smithsonian curator of natural-history rare books Leslie Overstreet, who, in the introduction to “America’s Other Audubon,†wrote:

“Even more, in our modern world of the professionalization of science, it may seem astonishing that amateurs like the Joneses could produce something scientifically important and lasting.â€Â Â

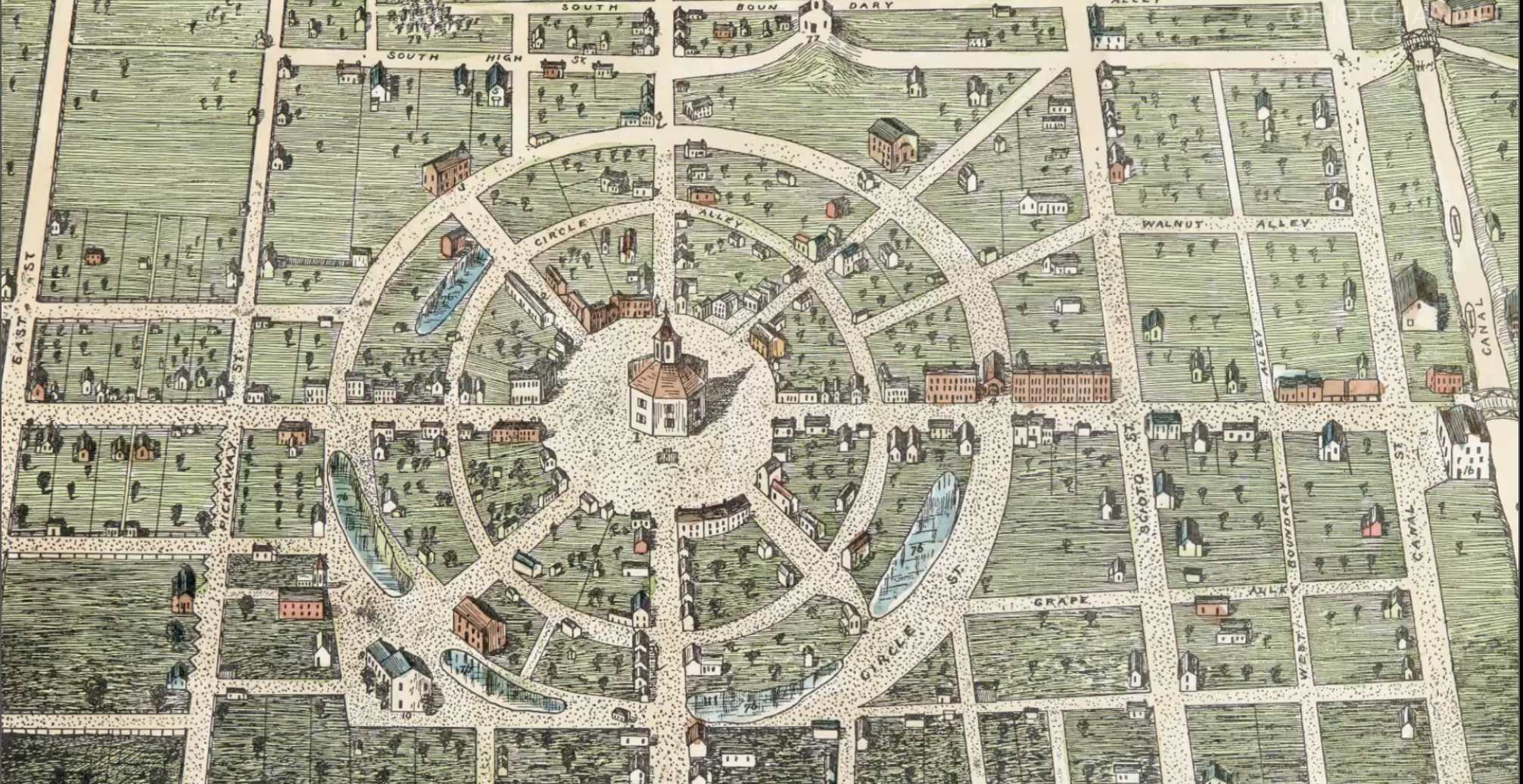

The Jones family, circa late 1800s. From left: Howard, Nelson, Genevieve, and Virginia. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

Appreciative of the meticulous drawings and curious about the family portrait, Kiser began to investigate. The outcome was “America’s Other Audubon,†(2012) which tells Genevieve’s poignant and heart-rending story that led to the family’s creation of a book that complemented naturalist John Audubon’s “The Birds of America,” which omitted eggs and nests.

The youngest child of country doctor with a consuming interest in birds, Genevieve was a happy, curious child who grew up in Circleville, Ohio, surrounded by wetlands and the Ohio and Erie canals. As a little girl, she joined her father, Nelson, when he visited patients, a habit that continued into adulthood. During those early buggy rides, Nelson taught her birding basics, and together they searched for nests and collected eggs, Kiser wrote.Â

Genevieve’s mother, Virginia, permitted her husband and children’s shared passion, only objecting when the songbirds the children raised or rescued and kept caged in their bedrooms woke the neighbors, Kiser wrote. In field notes, brother Howard described his experience with the ruby-throated hummingbird:

The nest of a ruby-throated hummingbird, illustrated by Virginia Jones. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

“The domestic life of the hummingbird is a model in every respect, and in strict harmony with the beautiful little home they occupy. In confinement the hummingbird soon becomes tame but always at a loss of health and spirits. In 1875 one came into my room through an open window and was captured without injury in a butterfly net. The little fellow was imprisoned. Here he remained until the following winter when he died, apparently of a broken heart.”

On one trip with her father, Genevieve found a nest that neither he nor Howard could identify, Kiser wrote. In researching, they discovered that no book yet existed, and so Genevieve decided to illustrate one, if Howard would collect the eggs and nests. Â

The blue jay “will steal every thing he wants to eat, and any thing he wants and cannot eat, he will carry off and hide. But to counterbalance this natural depravity, he is a pretty fair songster, his notes being low and sweet, in great contrast to his common catcalls,” Howard wrote. Illustrated by Virginia Jones. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

Childhood distractions, then school responsibilities, left the project incubating for years. Genevieve, both talented and bright, continued learning on her own after high school with the support from her brother, who shared his college coursework with her.

She was by nature anxious, a quality exacerbated during the Civil War when her father served as a surgeon for the Union Army. During this time she developed acne rosacea and became painfully self-conscious about her appearance, Kiser wrote.

Genevieve had a suitor 10 years older than her whose name remains unknown, but whose intellect and temperament suited her, Kiser wrote. However, he was a periodic drunk, which caused her parents to ask them not to marry for one year, during which time the suitor would remain sober. After several failed attempts, Genevieve was forced to break the engagement.

Unwed and isolated, Genevieve, now 30, grew despondent, Kiser wrote. The family knew her spirits must be raised, and, recalling the idea of the nest and egg book, urged her to take up the idea. In the past, her father had been reluctant to fund the costly project, but changed his mind. Kiser wrote:

“He felt so personally responsible for her anguish because he had pressured her to break off her engagement that he was compelled to help her initiate a project of her very own, one that would engage her passion for art and nature, and distract her from her sadness.â€Â Â

Genevieve at first planned to illustrate all 320 species of American birds but her father persuaded her to limit it to the 130 birds that nested in Ohio, which were common throughout the rest of the United States.

With help from her friend, Eliza Shulze, Genevieve drew and painted the eggs and nests collected by Howard, who also took field notes. Other friends and family became editors, fact-checkers and proofers.

Nest of an American robin, illustrated by Eliza Shulze. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

The plan was to produce 100 copies of the book, sold by subscription. The positive response to the first part resulted in increased subscriptions, including those of former U.S. President Rutherford Hayes and then-college student Theodore Roosevelt, Kiser wrote.

After personally completing five images, Genevieve contracted typhoid fever. Three weeks later she died. She was 32.

As the family grieved, the book’s future remained unknown. Weeks passed, until her mother decided to finish the project to honor and memorialize her daughter. The book, Kiser wrote, “became the Jones family’s transitional object, a physical entity with which they could distract themselves from their heartache and into which they could invest their passion and energy.â€Â

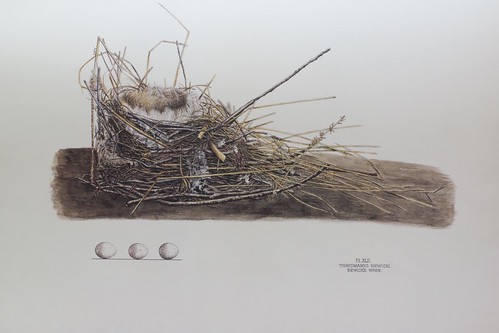

After Genevieve’s friends lost interest in the project and her suitor committed suicide, the family forged ahead, alone. Virginia poured all her love she could no longer give her daughter into illustrating the nests and eggs, wrote Kiser, explaining that Virginia had never drawn or painted anything with scientific accuracy, and had to learn the laborious process of lithograph. Kiser wrote:

“Despite her grief, she struggled with overcoming her casual artistic style and transformed herself into a scientific observer. Analysis and intellectual rigor were essential, because an artist does not draw what she sees, she draws what she understands.â€Â

Eventually, Virginia created lithographs as beautiful and meticulous, as lovely and exacting, as her daughter’s, Kiser wrote.

Bewick’s wren nest, illustrated by Virginia Jones. Image from “America’s Other Audubon” by Joy M. Kiser.

For two years, quarterly installments were issued on time until Virginia and Howard both got typhoid fever. They recovered, Kiser wrote, although Howard suffered heart damage and Virginia’s eyes were weakened. In 1886, the book was completed. In the introduction to “Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio,” Howard wrote:

“In their eggs, the birds center their whole existence. They work unceasingly and intelligently for a place where they can lay them, and guard them with their lives. Thus the nest, aside from its expression of ingenuity, skill, and patience, becomes an exponent of character.†Â

After his parents deaths, Howard locked the studio, which remained sealed for 32 years, and spent the rest of his life marketing the book, Kiser wrote. In the end, many copies were given to Howard’s children and grandchildren, one whom, overcome with curiosity, sawed off the lock to gain access to the studio. Only 26 complete hand-colored copies and eight uncolored or incomplete copies have been located. In 2010, one sold for $48,000.

Since its publication, scientists have appreciated the Jones’ family’s artwork and field notes as a rare and valuable reference tool. With “America’s Other Audubon,” the story of the family’s love, perseverance, dedication, and sacrifice now serves as a guide for all.

- “America’s Other Audubon”  (public library) by Joy M. Kiser.

- Smithsonian curator Leslie Overstreet.

- Naturalist John Audubon and the nest builders: wood thrush, ruby-throated hummingbird, blue jay, American robin, and Bewick’s wren.

- Lithography.

- Typhoid fever.

Leave a Reply